From The Rotarian by Frank Bures - On not being Scrooge

Thank you to Frank Bures who writes:

"As a freelance writer, I’ve never been what you’d call wealthy. But when I was growing up, my dad was a doctor, and we never worried about where our next meal would come from. Today I live in a neighborhood that is solidly middle class and diverse – in the color of the hybrid cars, if nothing else."

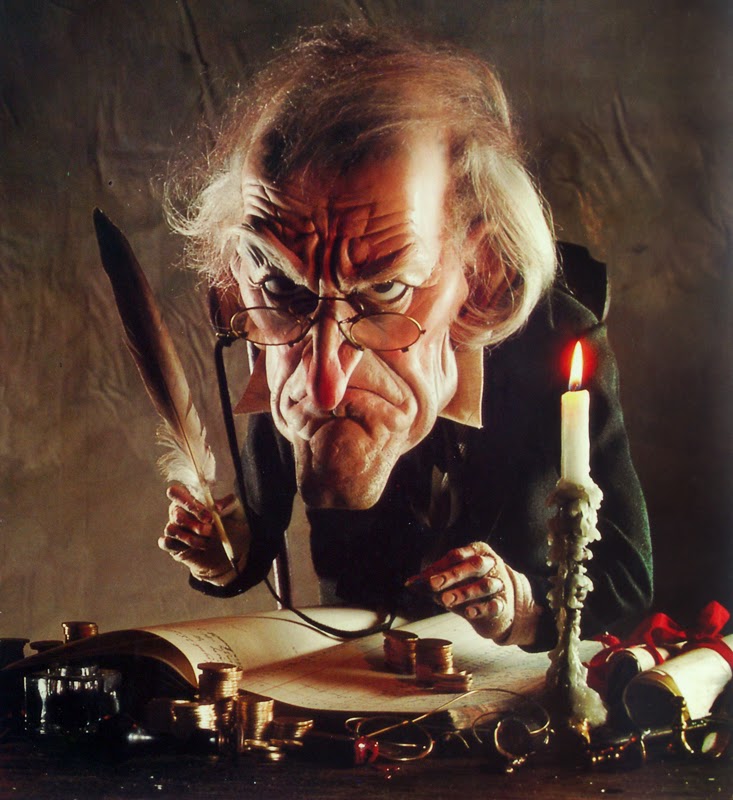

Am I living on an island? And could that be affecting my ability to see the plight of (a) guy in scraggly clothes? I’d always thought of myself more along the lines of Bob Cratchit. Now I had a miniature Jacob Marley (sitting) in my back seat, calling me Scrooge.

From Julie: Charles Dickens should've received a Nobel Prize for literature, by creating the Scrooge metaphor for miserliness. Unfortunately, the humanitarian awards began in 1895, well after the author's death in 1870. Nevertheless, I'd sure nominate him, posthumously, because his creation of Scrooge raised the bar for all of us who need reminders about how to improve our human condition.

On Not Being Scrooge by Frank Bures from December 2014 "The Rotarian"

"To build compassion, get out of your comfort zone."Down the road in front of me, the light turned red. As our car slowed, from the corner of my eye I saw a man standing in the middle of the street with a sign that said he was homeless and needed money.

My wife and two daughters were in the car with me. I looked straight ahead.

From behind me, a small voice spoke. “Can we give him some money?” It was my eight-year-old daughter. I didn’t answer. The light turned green, and I drove on. The voice spoke again.

“Why are you so mean, Daddy?” she said.

“Yeah,” my wife chimed in, smiling. “Why are you so mean?” She was sort of joking, sort of not.

My daughter continued: “How would you feel if you were a poor person and all you had was scraggly clothes and people just drove past you?”

“I don’t know,” I said. And honestly, I didn’t know how I would feel – let alone how that guy felt. In fact, I hadn’t thought about that sort of thing for some time. Back in college, for a senior project about homelessness, I’d played a homeless person in a movie. And I’d done some volunteering here and there, but in raising children lately, everything extraneous has been swept away.

For most of the year, it’s easy to get absorbed in our own lives. But the holidays are supposed to be different. This is the time when our thoughts are supposed to turn to others – to the people we buy gifts for, to those less fortunate than us. Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol plays on stages across the country. Every year, ghosts visit Ebenezer Scrooge and show him how hard his heart has become, and how little happiness all his wealth has brought him.

Wealth, in itself, is not a bad thing. It often helps you live longer and be healthier. It provides opportunities to see the world. It can fund an education and a place to live. But there can be a cost to having it as well, which research is now untangling. Paul Piff, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley, has co-published several studies that have found that wealthy individuals behave less “prosocially” than poorer ones. They give less of their money, percentage-wise, to charity. They feel less compassionate toward people in need. They are more likely to cheat on games (in a laboratory situation). And they are less attuned to the emotional states of others.

All of this seems to suggest, as F. Scott Fitzgerald once wrote, that the very rich are different from you and me (and not just because they have more money, as Ernest Hemingway quipped). But according to Piff, it’s not that they are different, it’s that being rich makes you different.

In studies that have temporarily altered the self-perceptions of low-income participants, making them feel better off, he says, “suddenly they start behaving as if they are actually wealthy. It’s not so much about wealthy people behaving in particular ways, but rather the experience of wealth making people behave in particular ways.”

But other research further complicates the subject. One “lost letter” study in London (in which letters were dropped to see how many people would mail them) showed that 87 percent of letters dropped in wealthier neighborhoods were mailed, while only 37 percent were mailed in poorer ones. And though that could be interpreted as looking out for one’s own, a Georgetown University study found that altruistic kidney donations (giving a kidney to a stranger) are more likely to take place in wealthy communities than poor ones, a finding that “paradoxically indicates that community-level income may positively predict prosociality even while individual-level wealth does not,” the authors wrote.

This is all complex – we humans, after all, are not so easy to figure out. But we may find a key in a 2012 study by the Chronicle of Philanthropy, which showed that when wealthy people live in more economically diverse ZIP codes, their charitable giving rises from an average of 2.8 percent to 4.2 percent.

Wealth isolates. Big houses. Big cars. No need to ask favors of people. Perhaps this is what underlies much of the shift in behavior among wealthy individuals. When we don’t need to interact with others, our ability to imagine their lives diminishes. Yet this is something Piff says we can easily reverse.

“In our lab work,” he says, “we find that wealthy people are less generous in general. But if you show them a brief video about child poverty around the world, they become just as generous as everyone else. So even brief reminders of the needs of others can build an inroad into this psychological island that you inhabit.”

As a freelance writer, I’ve never been what you’d call wealthy. But when I was growing up, my dad was a doctor, and we never worried about where our next meal would come from. Today I live in a neighborhood that is solidly middle class and diverse – in the color of the hybrid cars, if nothing else.

Am I living on an island? And could that be affecting my ability to see the plight of the guy in scraggly clothes? I’d always thought of myself more along the lines of Bob Cratchit. Now I had a miniature Jacob Marley in my back seat, calling me Scrooge.

I don’t want to be like that. I don’t want to suffer from what the writer George Saunders said was the thing in life he regretted most: failures of kindness. Maybe if it wasn’t too late for Scrooge, it wasn’t too late for me. I asked Piff about the best way to cultivate a more compassionate mindset.

“Just get out there,” he said. “Get out of your comfort zone. Have more contact with other people. The people who are the most satisfied with their lives are the ones who are the most embedded in their communities and who have engaged in acts of kindness and philanthropy. There’s a lot you can get out of being kind to others that money can’t buy you.” — Frank Bures

Labels: Ernest Hemingway, poor, rich

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home