Pope Leo XIV is American by birth with a genealogy rich in diversity and migration

Is Pope Leo my cousin?

Just hours after Pope Leo XIV (born Robert Francis Prevost in Chicago) made history as the first head of the Catholic Church from the United States, my aunt sent a Facebook post to our family group chat. It claimed the pope — who, at that point, was only known to have European ancestry — had “Creole of color roots from New Orleans on his mother’s side.”

As a Black Creole from a New Orleans Catholic family, I was excited. But as a journalist, I was skeptical.

The earliest record I found of Paul — an 1880 census from St. John the Baptist Parish — marks his race, along with that of his grandfather, parents, and siblings, as “mulatto.” The term, which denotes a person of mixed African and European descent, is considered offensive by many today because “mulatto” derives from the Spanish word used to describe mules.

But, young Paul and his family would not be permitted to identify as such for much longer.

Shortly after Union troops ended their occupation of Louisiana, former Confederates and their children reclaimed political power in the state and “promptly decided that they would institute a binary racial system,” Morlas Shannon said.

So Creoles of color were left with a choice: attempt to disappear into whiteness and the privilege it grants, or fully embrace their Blackness and the marginalization that accompanies it.

Sometime between 1908, and 1917, Paul and Agnes moved north to Illinois. Records seem to suggest Agnes’s parents, Gerard and Ernestine Martinez, and her aunt and uncle, Joseph and Louise Martinez (the pope‘s maternal grandparents), also made the migration around this time. Leo‘s mother, Mildred, was born in Chicago in 1911. Agnes Sorapuru is listed as Mildred’s godmother on the younger cousin’s 1912 baptismal record. Mildred’s middle name was also Agnes.

By 1900, Paul and his family had moved 40 miles downriver to New Orleans’ Seventh Ward, the cradle of the city’s Black Creole population. However, by then, Paul, his mother, and his younger siblings were all listed as “white” on the census.

Eight years later, 32-year-old Paul married 22-year-old Agnes Martinez, also a Creole of color living in the Seventh Ward, in the Catholic church.

According to 1920, census documents, the Sorapuru and Martinez families — all marked as white — lived fairly close to each other in Chicago. It also appears Paul and Agnes lived with her parents, Gerard and Ernestine Martinez, on, of all places, Orleans Street.

Fair-skinned Black people leaving their hometown only to reemerge elsewhere living as a white person is known as passing, or “passé blanc” in Louisiana.

For many, it was an act of economic, social, and personal survival, Gaudin said, not an expression of anti-Blackness. They “made a decision that racism is harmful, it can harm me and it can harm my children,” said Gaudin, who wrote a book about her Creole ancestors’ migration to California. “Moving out of Louisiana gave people the opportunity, if they wanted it, to be more ambiguous, or to be able to slip and slide across racial lines a little easier.”

But that privilege came at a cost. Passing usually meant “breaking the ties of family,” Peacock said, because the discovery of African ancestry “could harm your opportunities.”

By passing, Paul and the Martinezes cemented their collective identity shift from Black Creoles living in Jim Crow New Orleans to a family of white Catholics in cosmopolitan Chicago. The latter narrative is the one Leo and his brothers seemingly grew up on.

John Prevost, the middle brother who is two years older than the pope, recently told the New York Times he and his siblings always identified as white and didn’t discuss their Creole roots.

“It was never an issue,” the Times quoted him saying.

The pope and his siblings never met Paul Sorapuru. He died in 1948, a few years before the oldest Prevost brother, Louis, was born. Agnes outlived her husband by 20 years. The couple, according to surviving records, never had children of their own.

Paul‘s marriage into the Martinez family connected the branches of Leo‘s family tree to my own. But the decision to move to Chicago and pass created a branching moment that separated us from them.

My direct ancestors who stayed in Louisiana were shaped by their Black Creole identity. Growing up, we called our godparents by Louisiana French titles: Parrain and Nana or Nanny, short for Nénènn. My First Communion photos are still on display in my childhood home nearly 20 years later. My paternal grandmother, both parents, and my older sister are all proud graduates of the only historically Black Catholic university in the country, Xavier University of Louisiana, in New Orleans.

Despite their racial change, one thing the pope‘s ancestors retained from New Orleans was their Catholic faith. It was one of the few cultural identity markers from their old lives that was safe for them to hold onto.

Our fascination with Leo‘s Creole heritage shows how important race remains to our perceptions of people in America.

In 2006, at 55 years old, Roudané was going through the belongings of his recently deceased father when he came across a binder. Inside were ancestral photos and documents that revealed Roudané, who was raised white, had a long lineage of Afro-Creole ancestry.

“My heritage reappeared from this historical fog,” said Roudané, who currently runs a website dedicated to the legacy of the first Black daily newspaper in the United States, founded by his great-great-grandfather, Louis Charles Roudanez. “There was this whirlwind of emotion that left me with this undefinable realization that I was no longer who I thought I was.”

For Leo, Roudané said, there is an opportunity to use his platform as a world leader to make a difference about how we understand racial identity.

“I think the best thing that could happen from all of this new stuff that has come to light with the pope‘s ancestry is that he, and we, begin to really take a much more sophisticated look at what it means to be a human being,” Roudané said, “what it means to be Black, what it means to be white, what it means to be mixed race.”

So is the pope my “cousin”? Technically, no. My family member, Paul, is related to Pope Leo XIV by marriage, not by blood.

But in Black communities across America, family is largely defined by bonds, not by blood alone. The ties between our two families may have been severed a century ago — by migration, by circumstance, by racism — but the revelation of the pope‘s hidden heritage offers us a path toward reconciliation.

Julian E.J. Sorapuru can be reached at julian.sorapuru@globe.com. Follow him on X @JulianSorapuru.

Excellent feature article published in the Boston Globe by Julian Sorapuru: A Globe reporter saw his last name on the gravestone of the new pope’s grandparents.

|

| When reporter Julian Sorapuru saw his last name on the gravestone of Pope Leo XIV’s grandparents, he did some digging.Globe Staff/Jari Honora/Associated Press |

As a Black Creole from a New Orleans Catholic family, I was excited. But as a journalist, I was skeptical.

In moments of high public interest, misinformation tends to spread. But then my hometown newspaper wrote about it. Next came The New York Times, which ran a photo of the gravestone of Leo‘s maternal grandparents in Illinois.

But they weren’t buried alone. Other members of their extended family were also interred there and memorialized on the gravestone. Any doubt I had about the veracity of the pope‘s Creole heritage evaporated when I read my last name at the bottom of that gravestone.

Growing up with a last name as unique as Sorapuru — or “Soraparu,” as it’s spelled on the gravestone — my family always told me that if someone else shared it, we’re probably related.

So I immediately thought: Is Pope Leo my cousin?

But they weren’t buried alone. Other members of their extended family were also interred there and memorialized on the gravestone. Any doubt I had about the veracity of the pope‘s Creole heritage evaporated when I read my last name at the bottom of that gravestone.

Growing up with a last name as unique as Sorapuru — or “Soraparu,” as it’s spelled on the gravestone — my family always told me that if someone else shared it, we’re probably related.

So I immediately thought: Is Pope Leo my cousin?

The answer, which I’ll get back to, involves a winding tale mixed up in the muddiness of race. But first, some context.

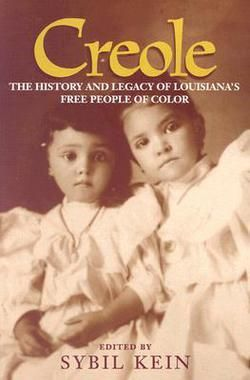

In modern popular culture, the word “Creole” has become shorthand to signify someone of mixed African and European heritage, usually with ancestral roots in Louisiana.

In modern popular culture, the word “Creole” has become shorthand to signify someone of mixed African and European heritage, usually with ancestral roots in Louisiana.

But, the term did not originate as a racial designation, said Mary Gehman, an independent historian who has written for more than three decades about free people of color in Southern Louisiana. Instead, she said, “it just meant something that was cultivated and developed in Louisiana, when it was under the French and Spanish,” which could apply to people, animals, and plants alike.

To understand how “Creole” became synonymous with race, we have to examine Louisiana’s pre-American history as a French, and later a Spanish, Catholic colony.

Compared with English American colonies, there was “a toleration and a recognition that there is this mixing that’s happening,” said Kent W. Peacock, a history professor and director of the Creole Heritage Center at Northwestern State University of Louisiana. There wasn’t “a full acceptance” of free mixed race people, he said, but they lived in a “space between the pure whites and enslaved Africans, and enslaved Indigenous folks.”

Many mixed-race people were designated free people of color and were permitted to seek things that were mostly denied to enslaved people like education, paid employment, property ownership — including that of other human beings — and legal protections.

The French and Spanish developed more laissez-faire attitudes toward racial mixing in comparison with the English for two reasons, Peacock said: The colony’s survival depended on it, and Catholic doctrine, which functioned both as religion and law, dictated that all people, regardless of race, had souls.

Although Louisiana functioned as a “tripartite” society, free mixed race people were still “a quandary,” said Wendy Gaudin, a professor at Xavier University of Louisiana, who specializes in Creole history. Despite speaking the same language, practicing similar customs, and often sharing ancestry, white Louisianans made it clear: “They’re not like us.”

After examining dozens of public records, mostly from the 19th century, I‘ve discovered my ancestry is filled with people who lived in this liminal space between fully realized humanity and complete dehumanization. But, that space slowly started to shrink after the Louisiana territory was sold to the United States in 1803. In the ensuing decades, as Americanization set in and the state transformed, so, too, did its racial ideas.

As the country grappled with the fallout of the Civil War, including the emancipation of enslaved people, “white people became very, very stringent about the question of race,” said Katy Morlas Shannon, a historian and author whose research focuses on the lives of enslaved people.

To understand how “Creole” became synonymous with race, we have to examine Louisiana’s pre-American history as a French, and later a Spanish, Catholic colony.

Compared with English American colonies, there was “a toleration and a recognition that there is this mixing that’s happening,” said Kent W. Peacock, a history professor and director of the Creole Heritage Center at Northwestern State University of Louisiana. There wasn’t “a full acceptance” of free mixed race people, he said, but they lived in a “space between the pure whites and enslaved Africans, and enslaved Indigenous folks.”

Many mixed-race people were designated free people of color and were permitted to seek things that were mostly denied to enslaved people like education, paid employment, property ownership — including that of other human beings — and legal protections.

The French and Spanish developed more laissez-faire attitudes toward racial mixing in comparison with the English for two reasons, Peacock said: The colony’s survival depended on it, and Catholic doctrine, which functioned both as religion and law, dictated that all people, regardless of race, had souls.

Although Louisiana functioned as a “tripartite” society, free mixed race people were still “a quandary,” said Wendy Gaudin, a professor at Xavier University of Louisiana, who specializes in Creole history. Despite speaking the same language, practicing similar customs, and often sharing ancestry, white Louisianans made it clear: “They’re not like us.”

After examining dozens of public records, mostly from the 19th century, I‘ve discovered my ancestry is filled with people who lived in this liminal space between fully realized humanity and complete dehumanization. But, that space slowly started to shrink after the Louisiana territory was sold to the United States in 1803. In the ensuing decades, as Americanization set in and the state transformed, so, too, did its racial ideas.

As the country grappled with the fallout of the Civil War, including the emancipation of enslaved people, “white people became very, very stringent about the question of race,” said Katy Morlas Shannon, a historian and author whose research focuses on the lives of enslaved people.

White Louisianans, many of whom had family members of African descent, stopped describing themselves as Creole, because, they “became nervous that white Americans would think they were people of color,” she said.

Newly empowered to vote, Black people obtained unprecedented political power in Louisiana by way of public office during the 12-year Reconstruction period after the war.

Newly empowered to vote, Black people obtained unprecedented political power in Louisiana by way of public office during the 12-year Reconstruction period after the war.

It was during this era, in 1875, that Joseph Paul Adolphe Sorapuru — my relative who is buried with the pope‘s maternal grandparents — was born in Louisiana.

Joseph, who went by Paul, is my first cousin four times removed. In other words, Paul‘s grandfather, Lorenzo Adolphe Sorapuru Sr., is my great-great-great-great-grandfather.

Joseph, who went by Paul, is my first cousin four times removed. In other words, Paul‘s grandfather, Lorenzo Adolphe Sorapuru Sr., is my great-great-great-great-grandfather.

The earliest record I found of Paul — an 1880 census from St. John the Baptist Parish — marks his race, along with that of his grandfather, parents, and siblings, as “mulatto.” The term, which denotes a person of mixed African and European descent, is considered offensive by many today because “mulatto” derives from the Spanish word used to describe mules.

But, young Paul and his family would not be permitted to identify as such for much longer.

Shortly after Union troops ended their occupation of Louisiana, former Confederates and their children reclaimed political power in the state and “promptly decided that they would institute a binary racial system,” Morlas Shannon said.

So Creoles of color were left with a choice: attempt to disappear into whiteness and the privilege it grants, or fully embrace their Blackness and the marginalization that accompanies it.

Sometime between 1908, and 1917, Paul and Agnes moved north to Illinois. Records seem to suggest Agnes’s parents, Gerard and Ernestine Martinez, and her aunt and uncle, Joseph and Louise Martinez (the pope‘s maternal grandparents), also made the migration around this time. Leo‘s mother, Mildred, was born in Chicago in 1911. Agnes Sorapuru is listed as Mildred’s godmother on the younger cousin’s 1912 baptismal record. Mildred’s middle name was also Agnes.

By 1900, Paul and his family had moved 40 miles downriver to New Orleans’ Seventh Ward, the cradle of the city’s Black Creole population. However, by then, Paul, his mother, and his younger siblings were all listed as “white” on the census.

Eight years later, 32-year-old Paul married 22-year-old Agnes Martinez, also a Creole of color living in the Seventh Ward, in the Catholic church.

According to 1920, census documents, the Sorapuru and Martinez families — all marked as white — lived fairly close to each other in Chicago. It also appears Paul and Agnes lived with her parents, Gerard and Ernestine Martinez, on, of all places, Orleans Street.

Fair-skinned Black people leaving their hometown only to reemerge elsewhere living as a white person is known as passing, or “passé blanc” in Louisiana.

For many, it was an act of economic, social, and personal survival, Gaudin said, not an expression of anti-Blackness. They “made a decision that racism is harmful, it can harm me and it can harm my children,” said Gaudin, who wrote a book about her Creole ancestors’ migration to California. “Moving out of Louisiana gave people the opportunity, if they wanted it, to be more ambiguous, or to be able to slip and slide across racial lines a little easier.”

But that privilege came at a cost. Passing usually meant “breaking the ties of family,” Peacock said, because the discovery of African ancestry “could harm your opportunities.”

By passing, Paul and the Martinezes cemented their collective identity shift from Black Creoles living in Jim Crow New Orleans to a family of white Catholics in cosmopolitan Chicago. The latter narrative is the one Leo and his brothers seemingly grew up on.

John Prevost, the middle brother who is two years older than the pope, recently told the New York Times he and his siblings always identified as white and didn’t discuss their Creole roots.

“It was never an issue,” the Times quoted him saying.

The pope and his siblings never met Paul Sorapuru. He died in 1948, a few years before the oldest Prevost brother, Louis, was born. Agnes outlived her husband by 20 years. The couple, according to surviving records, never had children of their own.

Paul‘s marriage into the Martinez family connected the branches of Leo‘s family tree to my own. But the decision to move to Chicago and pass created a branching moment that separated us from them.

My direct ancestors who stayed in Louisiana were shaped by their Black Creole identity. Growing up, we called our godparents by Louisiana French titles: Parrain and Nana or Nanny, short for Nénènn. My First Communion photos are still on display in my childhood home nearly 20 years later. My paternal grandmother, both parents, and my older sister are all proud graduates of the only historically Black Catholic university in the country, Xavier University of Louisiana, in New Orleans.

Despite their racial change, one thing the pope‘s ancestors retained from New Orleans was their Catholic faith. It was one of the few cultural identity markers from their old lives that was safe for them to hold onto.

Our fascination with Leo‘s Creole heritage shows how important race remains to our perceptions of people in America.

So far, he has not publicly acknowledged his African ancestry, but if he does, it would be more meaningful than a simple appeasing gesture.

“When people envision American Catholicism, they think of Boston, they think of New York,” said Jari C. Honora, the New Orleans genealogist who first publicly discovered the pope‘s Creole connections. “They don’t think of New Orleans as a very culturally and historically Catholic place, but it is, including the long history of Black Catholicism in the city.”

In Black communities, especially Catholic ones, from Chicago to Haiti many people are already treating the pope as one of our own.

“When people envision American Catholicism, they think of Boston, they think of New York,” said Jari C. Honora, the New Orleans genealogist who first publicly discovered the pope‘s Creole connections. “They don’t think of New Orleans as a very culturally and historically Catholic place, but it is, including the long history of Black Catholicism in the city.”

In Black communities, especially Catholic ones, from Chicago to Haiti many people are already treating the pope as one of our own.

(Maine Writer note here: The first settler who is credited with beginning the city of Chicago was a Haitian immigrant*.)

In fact, it is “an act of reclamation that comes from histories of oppression,” Gaudin said. The pope‘s ancestors’ passing was a form of “self-erasure,” she added, “so claiming them as Black is a kind of reversal of that erasure.”

Honora warned that racial identity is difficult to categorize. “People like to quantify race, and that is really impossible to do, even with the popular genetic tests,” he said. “Nobody can say, ‘You’re precisely 22 percent Black or white,’ because these things are social constructs.”

Mark Roudané relates to the pope‘s situation better than most.

Honora warned that racial identity is difficult to categorize. “People like to quantify race, and that is really impossible to do, even with the popular genetic tests,” he said. “Nobody can say, ‘You’re precisely 22 percent Black or white,’ because these things are social constructs.”

Mark Roudané relates to the pope‘s situation better than most.

In 2006, at 55 years old, Roudané was going through the belongings of his recently deceased father when he came across a binder. Inside were ancestral photos and documents that revealed Roudané, who was raised white, had a long lineage of Afro-Creole ancestry.

“My heritage reappeared from this historical fog,” said Roudané, who currently runs a website dedicated to the legacy of the first Black daily newspaper in the United States, founded by his great-great-grandfather, Louis Charles Roudanez. “There was this whirlwind of emotion that left me with this undefinable realization that I was no longer who I thought I was.”

For Leo, Roudané said, there is an opportunity to use his platform as a world leader to make a difference about how we understand racial identity.

“I think the best thing that could happen from all of this new stuff that has come to light with the pope‘s ancestry is that he, and we, begin to really take a much more sophisticated look at what it means to be a human being,” Roudané said, “what it means to be Black, what it means to be white, what it means to be mixed race.”

So is the pope my “cousin”? Technically, no. My family member, Paul, is related to Pope Leo XIV by marriage, not by blood.

But in Black communities across America, family is largely defined by bonds, not by blood alone. The ties between our two families may have been severed a century ago — by migration, by circumstance, by racism — but the revelation of the pope‘s hidden heritage offers us a path toward reconciliation.

Julian E.J. Sorapuru can be reached at julian.sorapuru@globe.com. Follow him on X @JulianSorapuru.

*AI- overview: The first known Haitian immigrant to settle what would become Chicago was Jean Baptiste Point du Sable. He is widely recognized as the first permanent non-Native settler and founder of Chicago. du Sable, born around 1750, established a trading post near the mouth of the Chicago River around the 1780s. He was believed to be of Haitian descent, with a French father and an enslaved African mother.

Maine Writer Post Script: Robert Francis Prevost is a beautiful example of the American melting pot, all in one family genealogy❗

Labels: Boston Globe, Catholic, Chicago, Creole, Julian Sorapuru, Martinez, New Orleans, Robert Francis Prevost

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home