Truth and Donald Trump is the epitome of an oxymoronic correlation

Those opposing prosecution say that such a meting out of justice would backfire, galvanizing Trump’s base. Some go so far as to suggest that seeing the former president “decked out in full orange, successfully prosecuted and dragged off to prison” would be a spectacle “more commonly associated with third world nations or undemocratic states.”

Growing up in Israel, in the shadow of the world’s longest-running conflict, I often considered whether it is better to forgo prosecution in favor of other forms of accountability and healing.

Some 30 years of research in transitional justice — the multidisciplinary study of how societies can constructively emerge from conflict and assert or reassert democratic values — provide evidence that, contrary to the understandable worry that a trial would be divisive, trials can instead help heal. In fact, they are considered one of the main methods to bring about “truth and reconciliation.”

The reasons trials help promote reconciliation are many. Trials are a performative affair. They are, among other things, a drama in which conflict is enacted and resolved. As such, they can compel attention in a way that pierces the disinformation bubble that has contributed to this era’s divisiveness. A trial of a former U.S. president is certain to be covered by news outlets that lean both right and left. The same would be true of a trial of a sitting president’s son, should federal prosecutors decide to charge Hunter Biden with tax crimes or a false statement related to a gun purchase.

Criminal trials are also easily understood by most, if not all, of the population. Consider how memorable and enduring was the trial of O.J. Simpson. Or recall President Bill Clinton’s infamous testimony about the nature of his relationship with Monica Lewinsky. Now, compare that with how impenetrable the Mueller report was, and how little traction its findings have found in the general discourse, let alone the popular imagination.

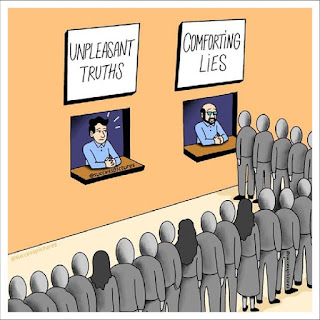

Trials are about the establishment of truth through evidence, beyond reasonable doubt. The truth gathered and amplified through the drama of a trial creates a historical record and shapes the collective memory. Trials are a stage upon which individuals with firsthand knowledge can be compelled to testify about what they know, and must do so truthfully under penalty of perjury.

Trials are as much about educating the public about wrongs that have been done as they are about seeking retribution for harms done (though they are about that as well).

At trial, the defendant gets to testify and be heard, and has the opportunity to compel the testimony of others. Milosevic, for instance, used his stage at The Hague to great effect. Any defense to alleged crimes that Trump — or, again, Hunter Biden — might testify to, without committing perjury, would similarly be amplified through the trial.

High-profile criminal trials should not be the only or the primary tool of reconciliation on our path to national healing. Bipartisan dialogue and resurrecting the tradition of appointing members of the opposing party to the Cabinet are examples of important measures that should be put into practice, no matter who holds office.

But the bar to clear for any decision to prosecute should not be any lower when it comes to former president Trump, or any other politician or politician’s family member, than the one for everyday Americans. Nor should the bar be any higher in a rule-of-law society, especially not in a divided country in need of truth and reconciliation.

Labels: evidence, justice, Maya Steinitz, The Washington Post